Dog breeding is looked upon controversially. Its opponents like to point to populated animal shelters and manifold dog misery in Germany and the world on the one hand and on the other hand – partly only rightly – to phenomena worthy of criticism in breeding just for beauty reasons, which sometimes grotesquely overemphasizes physical characteristics and loses sight of the dogs’ health.

Certainly, in breeds whose dams can hardly give birth naturally any more and are regularly dependent on a caesarean section, something has gone just as wrong as in extremely short-headed dogs that are always fighting death by suffocation, to name just two, admittedly extreme, examples.

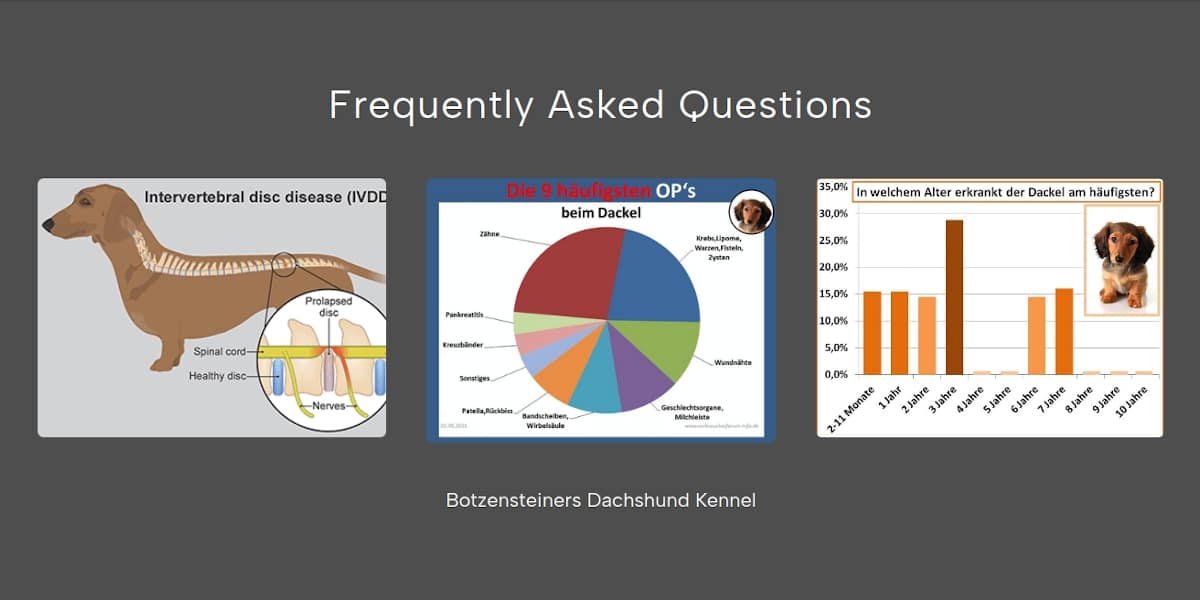

Smooth-haired dachshunds in particular are little affected by such problems. This is not necessarily because dachshund breeders are smarter than breeders of other breeds. The same can be observed in all breeds whose do actually still “work” in significant numbers. A “working” breed is somewhat immune to many aberrations to fashionable taste due to the physical demands of the work. However, Dachshunds belong to the rather long-lived dog breeds and may well reach an age of over 15 years. At an older age, around 8 years, Dachshunds should therefore also be regularly checked for diseases of the cardiovascular system, which can usually be controlled well with appropriate medication.

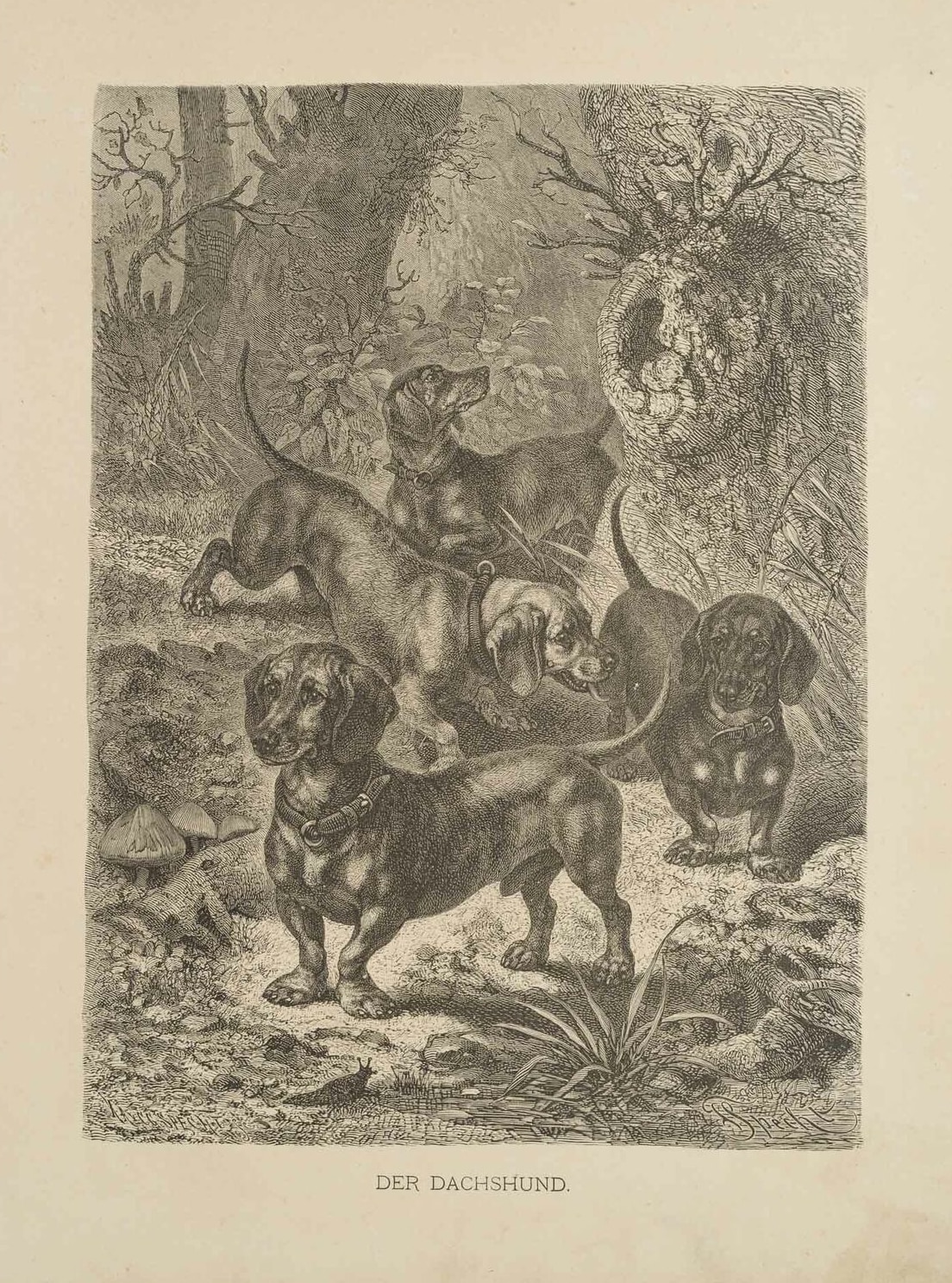

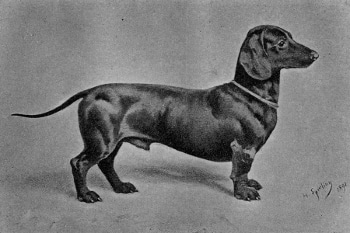

It is a widespread misconception that animal breeding, and especially dog breeding, is about “conservation” by reproducing a historical archetype over and over again. If you compare historical representations of early dachshunds with dachshunds of the 21st century, you will notice the differences. In breeding, one works towards an ideal, which is formulated for the Dachshund in FCI Breed Standard 148, and whose characteristics are hardly ever ideally combined in a dog. This standard is set by the DTK. The standard itself is not unchangeable or eternal. It has been and is regularly revised and then reformulates the future breeding objectives in parts, taking into account the actual state of the Dachshund breeds.

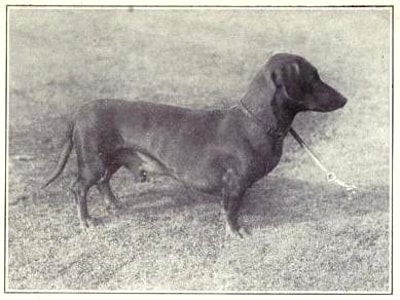

Dachshund | Dogs of all nations (1915)

The standard is one thing, but its interpretation is another. The interpretation is also changing and subject to certain fashions; after all, breeders, and even more so judges, who are only human, are always changing it. Thus, sometimes longer, sometimes shorter Dachshunds are preferred for first prizes and titles at shows; sometimes those with rather short and sometimes with rather long legs, etc. Despite the international standard, different types are favoured from country to country (or in the case of the British and Americans, who only distinguish between normal and miniature dachshunds and do not know any Rabbit Dachshund type, they are handled differently).

This room for interpretation is quite intentional. As already mentioned above, there is no such thing as “the” ideal-typical dog, which represents the breed standard 100% in all parts. There are only dogs that have developed within the breed standard or not. The latter are excluded from further breeding use. The remaining dogs, or their breeders and owners, then calmly fight over who comes closest to the ideal of the breed standard.

You will notice that the above mostly refers to the exterior, the so-called phenotype. Underlying this exterior is a gene repertoire. This not immediately visible equipment, the genotype, is in some respects much more important for the breeder. However, the knowledge of genetics – we are not excluding ourselves – is rather rudimentary among dog breeders. At the same time, it seems that “genetics” as a word has become a key stimulus and the testing for all possible traits, which is promoted by commercial suppliers, sometimes happens uncritically. It seems to us that this could also have something to do with the predominance of small dachshund-kennels in Germany.

It is certainly desirable that dogs and especially dachshunds are not bred in anonymous large kennels. On the other hand, one only learns through experience. But where is this supposed to come from if you only have a litter every two years? Certainly there is the possibility, at least through the VDH, to take part in breeders’ seminars and thus to get theoretical knowledge, but this cannot replace practical experience. So perhaps it can be explained that there is a growing tendency to rely on test procedures. However, this development also brings with it the danger of neglecting one’s senses or their use. For example, the progesterone test to determine the correct time for mating a bitch in heat certainly has its merits. On the other hand, however, this must not lead to a situation where a breeder is no longer in a position to estimate the correct mating day for his bitch with sufficient accuracy without a progesterone test.

Responsible pedigree breeding does not produce predictable results. However, it will provide you with a dog whose body, temperament and behavioural characteristics are within a predictable range. In the case of a young dog of uncertain origin or from a crossbreeding that may not be known exactly, you initially receive a surprise bag, the contents of which only become clear much later. The expectation that mixed-breed dogs are more robust or healthier than dogs from responsible breeding is deceptive. Just remember that the parents of mixed-breed dogs are usually pedigree dogs themselves. The hope that mixed-breed dogs from purebreds inherit only the good qualities of their parents is… naive.

When should my dachshund be neutered?

The Botzensteiners breeding community has given birth to many smooth-haired dachshunds since 2014. We are proud that our commitment has been honored by the German Dachshund Club with the Exhibition Breeder Pin in Gold.

You will find us near Berlin, about 50 km north-east of Alexanderplatz.

Brandenburg, Germany